Black Generational Wealth in the South: The Weight of History, the Promise of Policy

August 28th, 2025

By Sr. Policy Analyst, Dr. Regina Moorer

Generational wealth influences a family’s economic mobility as financial assets provide a head start, while their absence can lock a person into cycles of limited progress. Generational wealth refers to the assets, resources, and advantages that families can pass down from one generation to the next. It includes money, land, homes, and businesses, as well as access to education, social networks, and political influence. Who inherits opportunity and who inherits challenges often depends on the presence or absence of generational wealth. For many White families in the South, they benefit from wealth that has been accumulated and reinforced over centuries through property ownership, inheritances, and preferential access to credit and capital.[1] For Black families, however, those same opportunities were often blocked or lost due to slavery, Jim Crow laws, heirs’ property loopholes, redlining, and ongoing discrimination in housing and lending.[2] Even today, for many Black families in the South, that foundation remains fragile, eroded by systemic barriers and impacted by policy decisions.

The Deep Divide: Income Inequality and Household Wealth

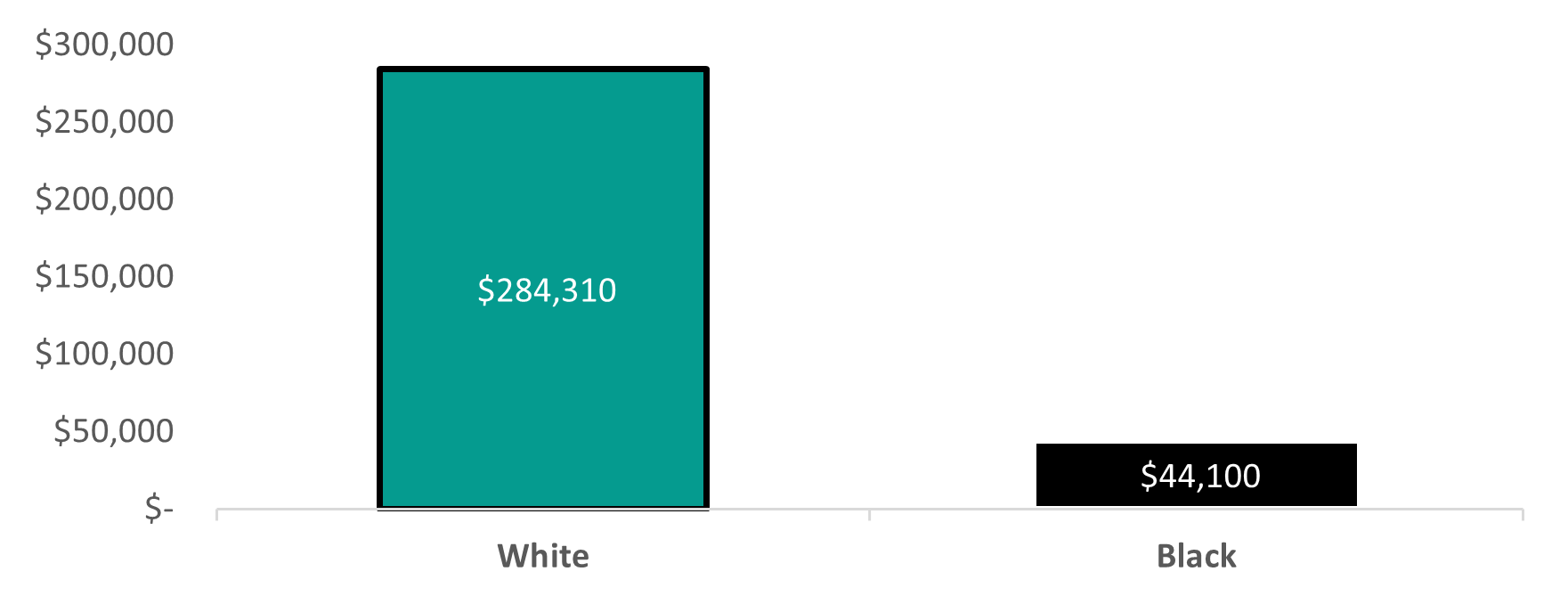

Wealth in America is not distributed evenly, and for Black families in the South, the imbalance is especially glaring. In 2022, the median White household held nearly $285,000 in wealth, compared to just $44,000 for the median Black household (See Figure 1).[3]

Figure 1: The National Racial Wealth Divide

The median White household holds over six times the wealth of the median Black household.

Source: “The Racial Wealth Gap 1992 to 2022.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

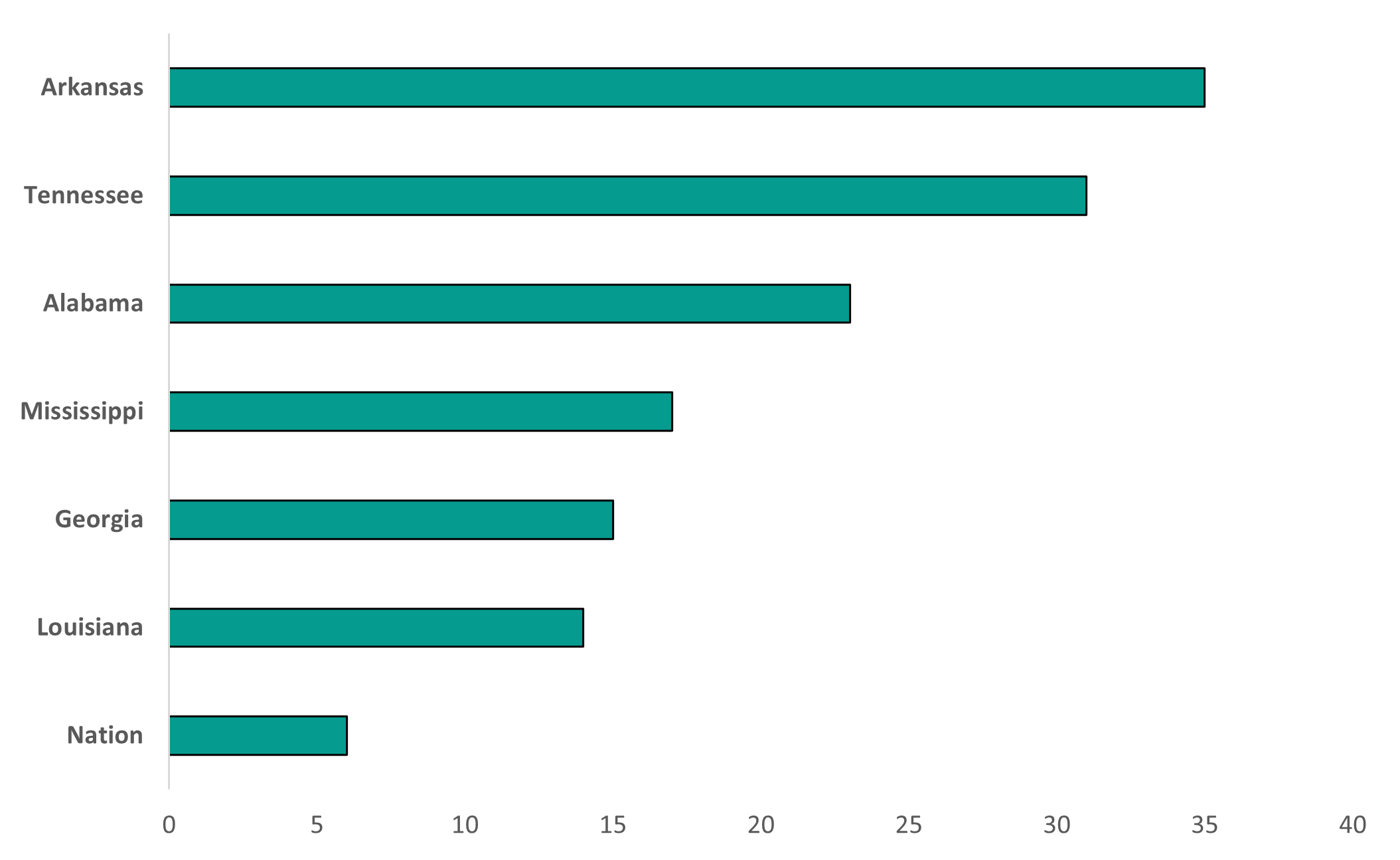

Although Black households make up more than 13 percent of the U.S. population, they control less than 5 percent of the nation’s wealth.[4] This disparity is reflected in the limits placed on a family’s ability to save for emergencies, invest in education, or build lasting security. Research from Kindred Futures underscores the depth of this crisis, showing that nearly two million Black households in the South live with zero or even negative net worth.[5] Consequently, the racial wealth gap is the South is substantial, reaching as high as 35:1 in Arkansas. White households in Arkansas have 35 times more wealth than Black households. (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Racial Wealth Gap Higher in Deep South States than Nation

White households hold up to 35 times more wealth than Black households in Deep South

Source: Kindred Futures. (2025). “Roots of Wealth: Unearthing Black Prosperity in the South”. https://kindredfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/RootsofWealth-R4.pdf

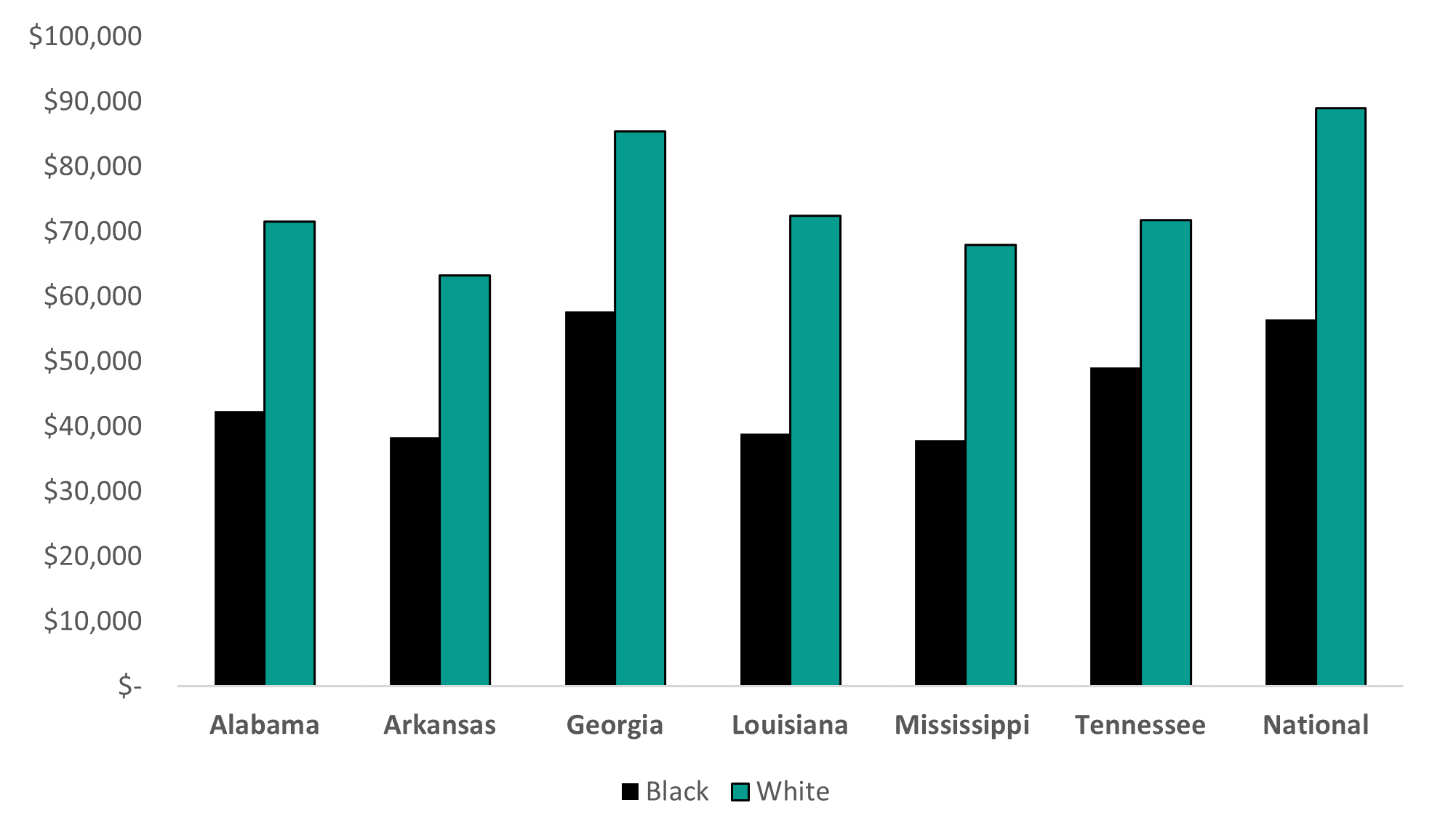

Recent data also show that White households consistently earn far more than Black households, both nationally and across the Deep South.[6] On average White households earn nearly $30,000 ($28,655) more than Black households which translates to more opportunities to save, invest, purchase a home, or start a business (See Figure 3). Without equal access to wealth-building opportunities, upward mobility remains relegated to certain demographics and inequality continues across generations.

Figure 3: The Deep Roots of the Racial Income Divide: Household Incomes by Race

White household incomes outpace Black households in the Deep South and Nation by average of $30,000

Source: US Census Bureau Quick Facts, 2024

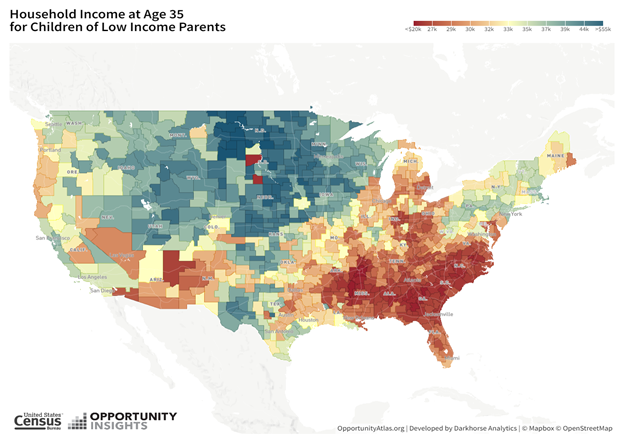

These disparities reveal how deeply structural inequities are embedded in the economy, shaping who can create generational wealth and who remains stuck in cycles of poverty and financial insecurity. Research from Opportunity Insights shows that generational wealth, or the lack thereof, affects the economic mobility of children. Economic mobility refers to the ability of individuals, families, or households to improve their economic status or move up the income ladder over time. It encompasses the upward or downward movement in income or wealth relative to one’s initial position. Children born to low-income households make less money (labeled red) than their parents in the Deep South and Southeast while children of low-income parents make more money than their parents (labeled blue) in the North and Midwest (See Map 1).[7]

Map 1: Economic Mobility is Lowest in the Deep South

Source: Opportunity Insights. (2018). https://www.opportunityatlas.org/

Addressing these inequities cannot rely solely on financial literacy or individual decisions; it requires policies that target the roots of inequality and broaden our understanding of wealth itself. The statistics clearly show the magnitude of the problem, but they also pave the way for solutions. By rethinking wealth through community-focused approaches and implementing bold policies, we can begin to repair what has been lost and forge a new path forward.

Wealth as Freedom: Insights from Kindred Futures

Policy can play a crucial role in changing this story. A promising example is the recent report by Kindred Futures on baby bonds in Georgia.[8] The idea is straightforward: establish publicly funded trust accounts for children, with contributions that accumulate over time. By age 18, a young person from a low-wealth family could have up to $16,000 for education, a home, or a business. For a single birth cohort in Georgia, such a program could generate $1.4 billion in new wealth. For Black families in the South, where traditional wealth transfers are often blocked, baby bonds offer a way to reset the starting point.

Kindred Futures’ recent report on wealth in the South provides a broader analysis of wealth.[9] Wealth isn’t just money. It also includes health, the environment, political participation, and freedom from predatory practices and products. Barriers to financial wealth lead to limitations in other areas, including reduced access to healthcare, fewer housing options, and weaker political influence.[10] When families have fewer resources, their ability to shape their future decreases.

Viewing wealth this way highlights that inequality is not only economic but also structural and civic. Overall, this approach points toward a future where public investment can transform individual opportunities and community well-being. Baby bonds exemplify how we can create structures that counter centuries of exclusion, utilizing tools that promote both stability and mobility.. Moving forward, the challenge is to design and implement policies that genuinely enable Black families in the South to inherit opportunity rather than loss, and to ensure that wealth in all its forms becomes a shared foundation, rather than a divided inheritance. By redefining wealth to include community well-being, it becomes possible to create conditions where Black families inherit not obstacles, but opportunity.

[1] Bean, Larry. 2023. “New Study: Inheritances Contribute Only Modestly to the Wealth Gap between White and Black Families.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. March 27, 2023. https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/news/2023/03/boston-fed-study-inheritances-contribute-modestly-wealth-gap-white-and-black-families.aspx.

[2] Ray, Rashawn, Andre M. Perry, David Harshbarger, Samantha Elizondo, and Alexandra Gibbons. 2021. “Homeownership, Racial Segregation, and Policy Solutions to Racial Wealth Equity.” Brookings. September 1, 2021. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/homeownership-racial-segregation-and-policies-for-racial-wealth-equity/.

[3] Dean, Joseph. 2024. “The Racial Wealth Gap 1992 to 2022.” National Community Reinvestment Coalition. October 30, 2024. https://ncrc.org/the-racial-wealth-gap-1992-to-2022/.

[4] Sullivan, Briana, Donald Hays, and Neil Bennett. 2024. “Households with a White, Non-Hispanic Householder Were Ten Times Wealthier than Those with a Black Householder in 2021.” Census.gov. April 23, 2024. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2024/04/wealth-by-race.html.

[5] Camardelle, Alex, Ph.D. “Juneteenth, Freedom’s Promise, and the Journey to Black Wealth in the South.” Kindred Futures, June 19, 2025. https://kindredfutures.org/juneteenth-freedoms-promise-and-the-journey-to-black-wealth-in-the-south-june-2025/

[6] Peterson Foundation. 2024. “Income and Wealth in the United States: An Overview of Recent Data.” Peterson Foundation. November 7, 2024. https://www.pgpf.org/article/income-and-wealth-in-the-united-states-an-overview-of-recent-data/.

[7] Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, and Sonya R. Porter. 2018. The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility. NBER Working Paper 25147. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. Accessible online at https://www.opportunityatlas.org/

[8] Camardelle, Alex. 2025. “How Baby Bonds Can Build Wealth and Transform Communities.”. https://kindredfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Securing-Georgias-Future_FINAL.pdf.

[9] Kindred Futures. (2025). “Roots of Wealth: Unearthing Black Prosperity in the South”. https://kindredfutures.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/RootsofWealth-R4.pdf

[10] “Our Approach.” 2024. AWBI Is Now Kindred Futures. November 4, 2024. https://kindredfutures.org/our-approach.