HOPE Opposes Proposed Changes to the Community Reinvestment Act

May 20th, 2020

The following is a summary of HOPE’s comment submitted to the OCC and FDIC in response to their proposed changes to the CRA.

Access HOPE’s full comment here.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) has been a critical, though imperfect, tool for HOPE to leverage the resources it needs to serve low-income communities, rural communities, and communities of color in the Deep South. Rooted in our experiences in serving communities that are frequently underserved by banks and our experience in utilizing the CRA to help do this work, HOPE is deeply troubled by the changes and urges a withdrawal of the current proposal.

The FDIC and OCC proposal, in the totality of its parts, essentially moves the CRA – and economic opportunity for our communities – further out of reach in three ways:

- Incenting larger, easier activities, potentially reducing the smaller, more intensive investments that Deep South communities so often need,

- Deprioritizing meaningful CRA activities in the country’s most distressed communities, and

- Diverting investments to activities far from the CRA’s original intent of redressing redlining.

In its comment to the FDIC and OCC, HOPE provided new analysis to highlight the proposal’s impact on the Deep South. Three of these analyses are summarized below, highlighting threats to investments in Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), small businesses owned by people of color, and underserved communities.

General Performance Standard Threatens CDFI Investments

A tangible consequence of the proposed General Performance Standard, both as a whole and its many problematic components, will be vanishing bank-motivated investments into CDFIs. To understand the importance of bank investments in CDFI capitalization, HOPE analyzed information reported by CDFI Fund awardees to the U.S. Treasury. Based on HOPE’s analysis of CDFI Fund Awardees from 2015 to 2017, bank investments accounted for nearly 20% of total capitalization – essentially $1 out of every $5 dollars of capital — compared to philanthropy which accounted for about 2%.[1]

This reliance on banks is more pronounced for CDFIs located in counties in which the majority of residents are people of color. Among the 315 CDFI Fund awardees in 2017, 40% of capital held by CDFIs in majority people of color counties came from banks, compared with just 2.3% from philanthropy. By contrast, CDFIs located in counties where the majority of residents are white, just 12.5% of their capitalization came from banks, with a similar 2.3% from philanthropy. Therefore, any drying up of bank-motivated investments into CDFIs is very likely to hit CDFIs in communities of color the hardest, and further reduce these organizations’ ability to lend and build wealth in the very communities in which banks otherwise are failing to serve.

Such changes will further exacerbate the investment gap for rural CDFIs. Rural CDFIs are already deeply underinvested in by banks, and the CRA proposal will widen this disparity. According to an analysis by the Opportunity Finance Network, only 29 cents of every dollar borrowed by rural CDFIs came from a bank. In contrast, over half of borrowed funds from urban CDFIs came from banks.[2]

Small Business Thresholds Threaten Investments in Small Businesses Owned by People of Color

HOPE urges the FDIC and OCC to reject the proposed increases for the small business revenue and loan sizes to $2 million, as well as the adjustment for inflation. The proposed increase to $2 million for both the definition of a small business and a small business loan is reflective of the proposal’s move to incent few, larger, easier transactions over the smaller, more nuanced investment on which our communities rely. HOPE echoes the concerns raised in the comment submitted by the Expanding Black Business Credit Initiative (EBBC) that “[a]ny move to incentivize larger loans to larger businesses, as the proposal does, will disproportionately benefit white-owned businesses over Black-owned businesses.”[3]

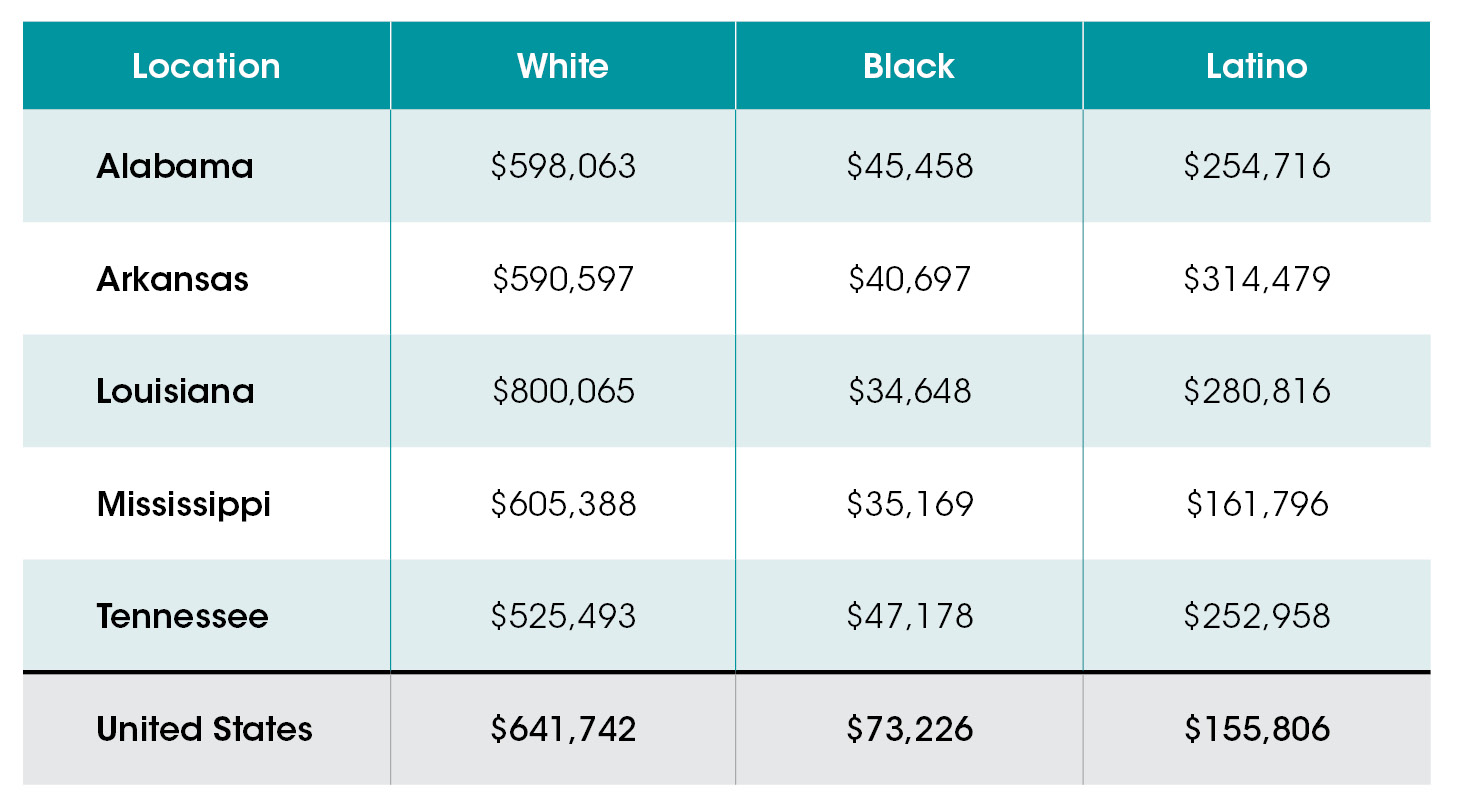

As the EBBC notes, nationally, “In terms of revenue (as measured by annual receipts) white owned business, have over $640,000 in annual receipts, dwarfing that of businesses of color ($160,000) and Black-owned businesses ($73,000).” These disparities persist throughout our region. See Table 1.

Table 1: Business Value by Owner Race/Ethnicity in the Deep South[4]

HOPE’s own lending experience confirms that supporting small business owners in the Deep South generally requires loans significantly lower than $1 million, and a significant number of our borrowers had revenues less than $1 million. Between 2017 and 2019, 88% of HOPE’s business loans (excluding NMTC project loans) were under $1 million. Even including NMTC project loans, 72% were under $1 million. In 2019, 78 (68%) out of 114 HOPE business borrowers had gross revenues less than $1 million. Finally, HOPE launched a new small business product in March 2020. Based on HOPE’s analysis of the demands and needs in our region, this product will have a maximum loan size of $100,000.

The harm of the proposed increase to $2 million is further exacerbated by other changes in this proposal, including the use of dollar amounts as measurement of activity rather than units, the balance sheet evaluation, and potential for banks to receive a passing grade even if they are not adequately serving half of the bank’s assessment areas.

Assessment Area Proposals Threaten to Leave Behind Underserved Communities

There are a number of problematic proposed changes related to assessment areas. These include contemplating banks to fail in half of their markets, but still receive a passing grade; using only bank deposits to determine banks’ assessment areas; and allowing bank investments in areas outside of their assessment areas to count towards their CRA requirements without ensuring that those investments target economically distressed communities. While HOPE is glad to see the proposal recognize the need for banks to have CRA obligations in other areas in addition to where their branches are located, the proposal misses the mark for benefitting Deep South communities.

For example, the proposed deposit-only concentration as a way to determine assessment areas beyond bank branch locations will not reach already underserved communities. By their very nature, low-income communities have very little money and therefore very few deposits. The small Delta town of Itta Bena, Mississippi, where HOPE is the only depository institution, provides a good example. Itta Bena has 42% poverty rate, median income of about $20,000, and 91% of its residents are Black. HOPE estimates the total deposit potential in Itta Bena is approximately $1.1 million. It will be nearly impossible for such areas to comprise a five percent concentration of a banking institution’s total deposits.

To gauge how the deposit-only concentration would affect low-income communities and communities of color throughout the country, HOPE analyzed data from the FDIC deposit database.[5] The data allows for an examination of deposit-levels in certain communities, and whether they might comprise five percent of a bank’s total deposits. This serves as a type of proxy to assess whether these communities would be included in the deposit-only assessment areas as contemplated by the proposal.

In this analysis of 2019 data, HOPE found that overwhelming low-income communities and communities of color would likely not benefit from the assessment areas based on the proposed deposit-only concentration because of the low-level of deposits in these regions:

- 71% of branches in persistent poverty counties had deposits totaling less than five percent of their bank’s deposits.

- 88% of branches located in counties where the majority of residents are people of color had deposits totaling less than five percent of their bank’s deposits.

Conclusion

The Deep South is home to more than 100 counties which have been locked in persistent poverty for more than half a century, due to a wide range of policies focused on the extraction of wealth among low-income people and people of color. The CRA, while imperfect, has been an important tool for catalyzing investment in these communities, often existing beyond the reach of traditional bank business models. Unfortunately, under the OCC and FDIC proposal, deep concerns arise as to whether those investments would have ever occurred in the first place and the anticipation of less investment in the least economically mobile region of the country. Ultimately, the proposal widens the wealth gap and further inhibits economic opportunity in already hard-pressed areas of the country, particularly here in the Deep South, and, as such, the OCC and FDIC should withdraw this proposal.

[1] Hope Policy Institute analysis of data from CDFI Fund, ReleaseILR_fy03_017, https://www.cdfifund.gov/Documents/FY%202017%20Data,%20Documentation,%20Instructions.zip [2] Bank Investment Falls Short in Rural Areas. Opportunity Finance Network. February 2019. https://ofn.org/sites/default/files/resources/PDFs/Policy%20Docs/2019/OPP_054%20-%20One%20Pager%20Handout%20CRA_FINAL%20Feb%202019.pdf. [3] Expanding Black Business Capital Initiative, Comments to the OCC Regarding Community Reinvestment Act Regulations, Docket ID OCC-2018-0008, March 11, 2020 [4] Prosperity Now, Scorecard: Business Value by Race, data from the 2012 Survey of Business Owners.: U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, 2015 https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by-issue#jobs/outcome/business-value-by-race [5] Hope Policy Institute analysis of data from FDIC Summary of Deposits/Branch Office Deposits https://www7.fdic.gov/sod/dynaDownload.asp?barItem=6 calculating the percent of institutional deposits represented by each bank branch located in Persistent Poverty Counties (data from the CDFI fund) and counties with a majority of people of color (calculated using data from the U.S. Census).