Deep South Advocates Lift Up Strategies to Remove the Barriers of Criminal Justice Debt

May 4th, 2021

By Calandra Davis, Policy Analyst

On April 1, 2021, Hope Policy Institute and the Southern Economic Advancement Project hosted a webinar, “Examining the Intersection of Criminal Justice Debt and Economic Opportunity in the Deep South” featuring the Southern Center for Human Rights, the Sycamore Institute, Alabama Appleseed, and DeCarcerate AR. The discussion continued the efforts to explore the interlocking systems of imprisonment and economic inequality that block people who are formerly incarcerated from reaching sustained levels of financial mobility and thus preventing successful re-entry. This webinar follows Hope Policy Institute’s most recent report, Examining the Intersection of Criminal Justice and Financial Services in the Deep South. Both the report and webinar are rooted in not only the data and analysis of federal criminal justice related debt in the Deep South, but also in the experiences of those impacted by the criminal system.

The webinar focused primarily on the barriers of and solutions to criminal justice debt in the Deep South. This criminal justice-related debt, which is largely comprised of legally binding financial obligations, and other fines and fees, is imposed on people interacting with the courts, jails, and prison systems. As just one example, a new report from the Sycamore Institute, Fees, Fines, and Criminal Justice in Tennessee, provides an in-depth analysis of the complicated systems and dollar flows of fines and fees, in one Deep South state, Tennessee. The report documents the mounting costs imposed by Tennessee’s criminal justice system, finding more than 360 types of fines and fees imposed by the state and local governments.

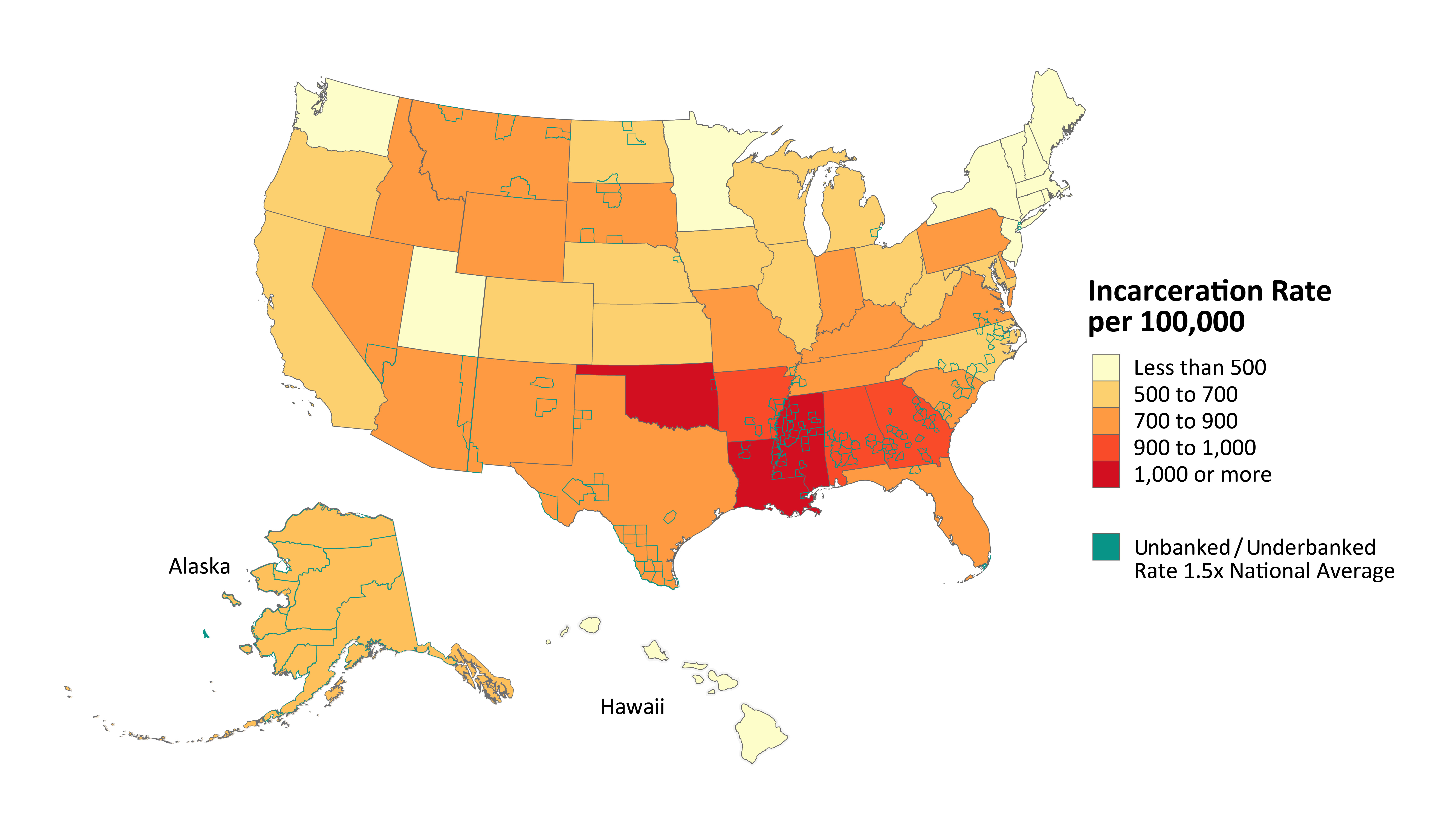

It is important and necessary to focus this conversation on the Deep South region. Four of the 10 states with the highest incarceration rates in the country are in this region.[1] People and policy makers may often think about the criminal justice and financial system as two separate systems. Figure 1 shows how these systems interlock. Debt is connected to both the high incarceration rates and the high un- and underbanked household rates. Unbanked households are defined as not having a savings or checking account with a financial institution. In one majority Black Alabama county, Jefferson County, the state prison incarceration rate surpasses the national rate at 627 per 100,000 residents.[2] In 2017, the same county also holds a combined high rate of underbanked and unbanked households at 29.5%.[3] At that same time, the national rate of underbanked and unbanked households was 25.2%.[4]

Figure 1. State Incarceration Rates and County Un/Underbanked Household Rate

There is a long, costly history that binds criminal and economic injustices. The costs and impacts are highly concentrated in communities already stricken with persistent poverty. In 2019, people in the Deep South, home to one-third of the nation’s persistent poverty counties, were burdened by more than $4 billion in debt related to their interaction with the federal criminal system, more than double than what it was 10 years ago.[5] Formerly incarcerated individuals pay their debts to society twice, once by serving out their sentences and again by carrying the burden of heavy debts upon release.

There are severe and concrete examples of the consequences of this debt. For example, these debts are often used to re-incarcerate people, prevent people from voting, and revoke state driver’s licenses. Additionally, in the South where access to public transportation is limited, licenses are not just significant for opening accounts but also critical for getting back and forth to work. In their report, Stalled, Alabama Appleseed highlights the harm of driver’s license revocation when people are unable to pay their fines and fees. The report draws its analysis from a 2018 survey of Alabamians whose licenses were suspended due to unpaid tickets. Nearly half of the survey respondents took out a high-interest payday loan to pay off their tickets and nearly two-thirds were jailed in connection with unpaid traffic debt.

The debt burden exacerbates the challenges people are facing when re-entering society. During the webinar, a mom impacted by the criminal system and working with DeCarcerate AR shared her story about the mountains of medical debt that grew while she was incarcerated. Even though the Department of Corrections contracts with a private company for medical services, she receives the bills from the debt collectors. More of these stories are documented in HOPE’s report and are far too common throughout the South.

Whether those debts are accumulated before or during incarceration, they follow individuals long after their release and in many instances bring them right back into the criminal system. Another example of debt accumulation while incarcerated can be seen by taking a closer look at multiple Alabama counties. Incarcerated individuals are personally billed for their healthcare needs, and their bills can end up with collection agencies while they have no source of income, wreaking havoc on their credit.[6] Family members also often take up the burden of paying the debt to ensure the health care needs of their loved ones continue.

For Mississippians, the inability to pay the debts associated with criminal justice monetary sanctions often leads to re-incarceration. In fact, there are four restitution centers across the state serving as debtor’s prisons where formerly incarcerated individuals work to earn money to pay off court-ordered debts. Though half of the people housed at the centers owe less than $3,500 in debt, they stay four months, on average, and sometimes years working to satisfy debts.[7]

One thing is clear: it does not have to be this way. Take a moment to imagine what else might be possible if people were paying this money towards a down payment for a home for their family, or small business start ups or even transportation to get to and from work rather than giving this money to these extractive debt mechanisms. Debt is just one small piece of the puzzle. Yet the puzzle cannot be solved without tackling the issue of debt.

The good news is that there are solutions to these issues. Policy makers must consider economic equality in their decision making to ensure the criminal justice system is less punitive and more equitable. Policies that champion debt reduction are particularly important for formerly incarcerated persons who are more likely to encounter predatory lending practices and lack access to credit. To this end, policy makers should:

- Ease debt collection practices and prevent the accumulation of debt during incarceration.

- Set caps on criminal justice debt to waive fees and fines of low-income individuals involved in the justice system.

- Prohibit the revocation of driver’s licenses for unpaid fines and fees.

Watch the full webinar here to hear from other panelists and learn more about the intersection of the criminal justice debt and economic opportunity.

[1] Sawyer, Wendy. Wagner, Peter. States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2018. June 2018.

https://www.prisonpolicy.org/global/2018.html

[2] Widra, Emily. How America’s Major Urban Centers Compare on Incarceration Rates. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/03/28/urban-incarceration/

[3] Prosperity Now Scorecard, “Data by Location: Jefferson County, AL “https://scorecard.prosperitynow.org/data-by location#county/1073

[4] FDIC, 2019 How America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services, available at www.economicinclusion.gov.

[5] United States Attorneys’ Annual Statistical Report. 2019. https://www.justice.gov/usao/page/file/1285951/download

[6] Sheets, Connor. How Some Sheriffs Force Their Inmates Into Medical Debt. Dec 26 2019. https://www.propublica.org/ article/how-some-sheriffs-force-their-inmates-into-medical-debt

[7] Wolfe, Anna. Liu, Michelle. Think Debtors Prisons Are a Thing of the Past? Not in Mississippi. https://www. themarshallproject.org/2020/01/09/think-debtors-prisons-are-a-thing-of-the-past-not-in-mississippi