On the Fight for Economic Justice: Stories of Resiliency, Ingenuity, & HOPE in the Deep South

February 1st, 2023

By Courtney Thomas, Senior Policy Analyst

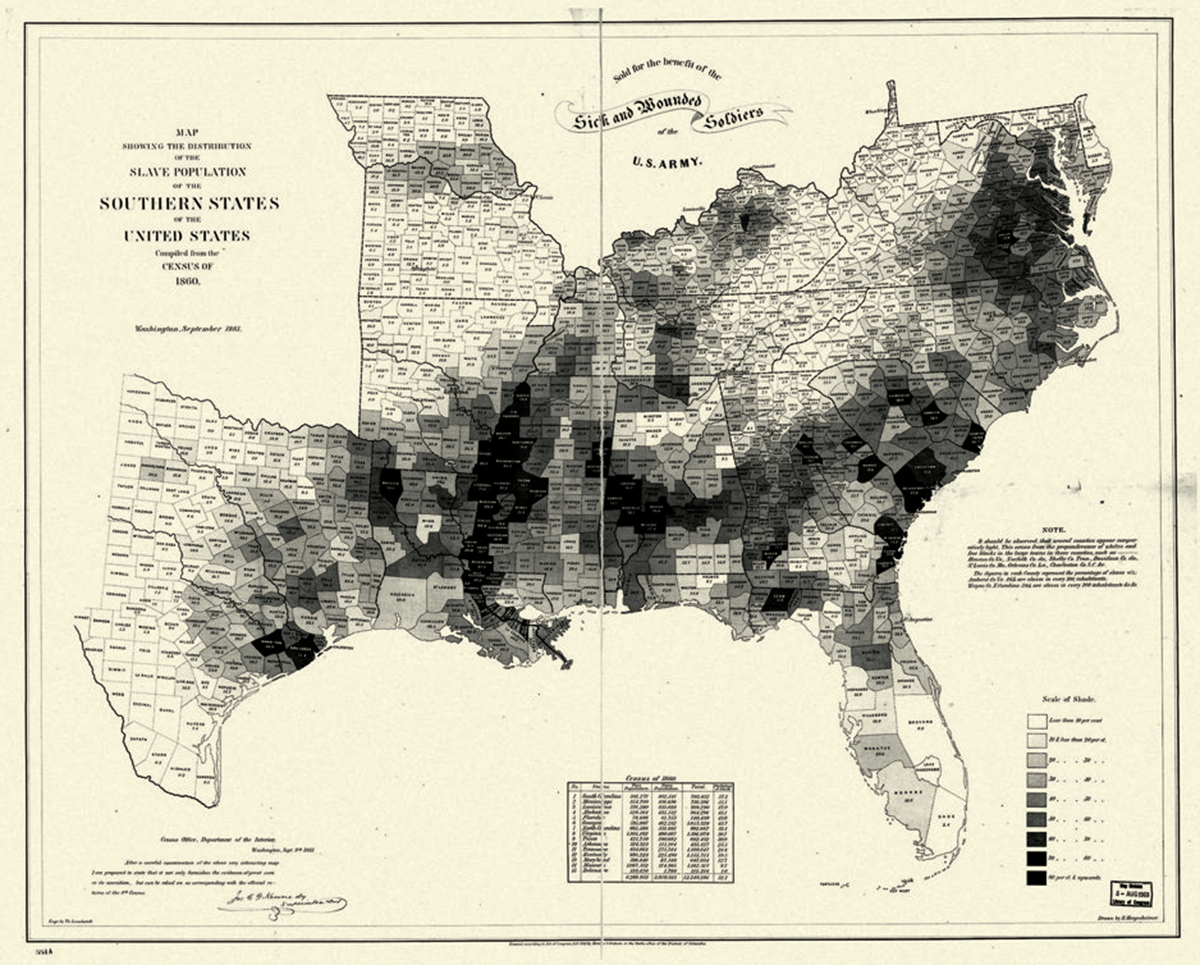

Apart from being a cultural mecca of vibrant music, delicious food, rich arts, and culture, the Deep South is characterized by a history of economic exclusion and racial degradation, especially for Black neighborhoods and communities. From chattel slavery to Jim Crow, racist, state-sanctioned policies have had long-term effects on economic and social inequities that persist within the region. The Deep South, consequentially, has the highest concentration of persistent poverty in the nation today. Approximately one-third of persistent poverty counties in the nation are located in the Deep South states of Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee.[1] Persistent poverty areas have been shown to exhibit the highest rates of unemployment, lowest rates of banking access, and the poorest health outcomes.[2] An examination of the 1860 Census also demonstrates that race and place are inextricably and historically linked. In many of these same communities, the Black and Brown populations remain the majority.

Map 1: Highest Concentrations of Slave Populations in the Deep South, Southeast U.S.

Source: Hergesheimer, E. (1861). “Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the southern states of the United States Compiled from the Census of 1860”. Washington, Henry S. Graham. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99447026/

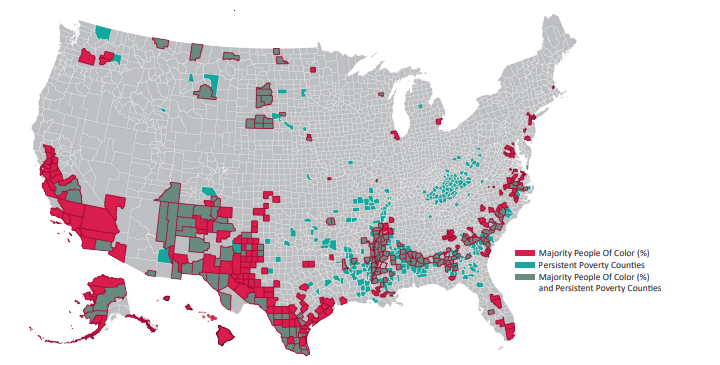

The majority (60%) of people living in persistent poverty counties are people of color, and four out of ten persistent poverty counties are majority people of color. [3]

Map 2: Race, Place, and Persistent Poverty are Inextricably Connected

Source: U.S. Census American Community Survey. (2019). U.S. Treasury CDFI Persistent Poverty counties (February 2020). HOPE Policy Analysis

Against this backdrop, leaders known and unknown rose to address injustices and improve the social and economic conditions of Black people. Their contributions and sacrifices have laid the foundation for which HOPE and other Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs) find their mission — increasing economic mobility and security among historically marginalized communities.[4]

Many have fought for economic justice and stability in the heart of the Deep South, that is, the Mississippi Delta. Two were most notable. Fannie Lou Hamer and Unita Blackwell, both Black women civil rights leaders, worked to alleviate rural poverty and increase economic stability through policy change, infrastructure improvement, and increased opportunities for self-sufficiency within Black communities. Fannie Lou Hamer understood that economic security was fundamental to the Civil Rights Movement and advocated for financial freedom and economic autonomy. In 1967, she founded the Freedom Farm Cooperative, which provided opportunities for Black families who were traditionally excluded from land ownership to produce food and crops. The cooperative expanded to include programming for education, clothing, and affordable housing for up to 70 families.[5]

Unita Blackwell was a sharp critic of racial and economic inequality within the Mississippi Delta. Born to sharecroppers, she used her voice to create policy change and win funding for neighborhoods. She served as the first Black woman mayor of Mississippi, and through her efforts, she was able to win federal grant money for the city of Mayersville to obtain a police and fire department, a public water system, paved streets, housing for the elderly and disabled, and other crucial infrastructure improvements. [6] Such investments boost the local economy by connecting residents to wealth-generating opportunities and creating healthy neighborhoods where individuals can live, work, and prosper.

The mission of HOPE builds on the legacy of these great civil rights heroes, but despite their contributions, many challenges remain. There have been many efforts to pass policies that correct the inequities of the past, yet access to banking and financial services remains unequally distributed by race. Black families are more likely to be unbanked or underbanked and fall victim to predatory lenders that offer high-cost loans and drain resources from their communities. Financial investments in the Deep South lag across the U.S., and individuals and businesses lack access to capital to build their economies and generate wealth within their neighborhoods. Whether it is offering a loan to a small business or opening up a bank account for a consumer for the first time, HOPE works to improve the lives of underserved households within the region.

Like Fannie Lou Hamer and Unita Blackwell, HOPE recognizes that access to capital is key to greater economic opportunity and financial stability for families. Since 1994, HOPE has generated over $3.6 billion in financing and related services for the unbanked and underbanked, homeowners, entrepreneurs and small business owners, nonprofit organizations, health care providers, and other community and economic development purposes. Collectively these projects have benefited more than 2 million individuals throughout the Deep South. Through initiatives like the HOPE Community Partnership, HOPE collaborates with municipal leaders to provide capacity building, project management, and grant support for rural towns to receive funding for neighborhood improvements. In this work, HOPE has partnered with the first Black mayor of Jackson, MS, and founder of the Mississippi Institute for Small Town, for which the HOPE Community partnership is modeled, Harvey Johnson, to assist municipalities in accessing public and private funds for community development.

HOPE also provides access to wealth-building opportunities and protection for those people and neighborhoods who have been traditionally excluded from mainstream financial institutions. This is evidenced through a borrower’s story in Memphis, TN.

Turned down by three banks, a divorced mother of two was living paycheck to paycheck when her car needed an emergency repair. “I thought the payday loan was a source of survival, but the interest rate was eating me up,” she says. After hearing a radio advertisement about HOPE, she decided to visit a branch near her home. HOPE was able to replace her high-interest debt with an affordable low-interest credit-building loan.”

Increasing access to capital and financial stability is an extension of the civil rights movement. Lack of capital, poor infrastructure, and critical community services preclude a person’s ability to meaningfully participate in society and build wealth. HOPE works to combat social and economic injustice and build on the efforts of bold, resilient, and creative community activists and organizations. Myrlie Evers-Williams, civil rights leader and wife of Medgar Evers, the first field secretary of the NAACP, notes that “HOPE provides people with access to self-determination, and economic empowerment, and dignity. That is exactly what Medgar wanted.” [7]

In the upcoming weeks, HOPE Policy will continue to reflect on key developments and contributions within Black history. Although those historical moments have passed, the fight for economic justice persists in the Deep South, with HOPE for a brighter future.

[1] HOPE Policy Institute Analysis. (2023). CDFI Fund Persistent Poverty Counties February 2020. https://binged.it/3HmC84q. Accessed January 2023.

[2] Partners for Rural Transformation (2019). “Transforming Persistent Poverty in America: How Community Development Financial Institutions Drive Economic Opportunity.” https://fahe.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy-Paper-PRT-FINAL-11-14-19.pdf

[3] Id.

[4] Kiyadh Burt. (2021). “The Legacy of Black Collective Economic Development.” HOPE Policy institute. http://hopepolicy.org/blog/the-legacy-of-black-collective-economic-development/

[5] Blain, Keisha. (2021). “Black Political Rights Can’t Be Divorced From Economic Justice. Why Fannie Lou Hamer’s Message and Fight Endure Today “Accessed January 2023. https://time.com/6109598/fannie-lou-hamer-economic-justice-civil-rights/

[6] Carey, Mia L. “Unita Zelma Blackwell (1993-2019)”. U.S. National Park Service. Accessed January 2023. https://www.nps.gov/people/unitablackwell-1933-2019.htm

[7] HOPE Credit Union. (2020). “Barrier Breakers: Myrlie Evers-Williams & William Winter.” https://hopecu.org/stories/barrier-breakers-myrlie-evers-williams-william-winter/