Stronger Together: How CDFIs and HBCUs Build Lasting Change

August 21st, 2025

Dr. Regina Moorer, Sr. Policy Analyst

Stepping onto the campuses of Tougaloo College in Mississippi or Talladega College in Alabama means entering institutions that extend far beyond the traditional role of higher education. These colleges have fueled civil rights movements, trained generations of leaders, and served as vital lifelines for their surrounding communities. Yet, like many Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), they embody a paradox: an outsized impact sustained despite undersized resources.

This is where Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) like HOPE step in. Together, CDFIs and HBCUs form partnerships that are rewriting the future of the Deep South.

The Shared Mission

HBCUs have always stood at the intersection of education, culture, and justice. Beyond academics, they are anchor institutions that generate jobs, nurture small businesses, and preserve Black history. Their influence is evident — 80 percent of Black judges, 50 percent of Black doctors, and 40 percent of Black engineers are HBCU graduates.[1] Collectively, HBCUs drive nearly $15 billion in annual economic impact and support over 134,000 jobs.[2]

CDFIs like HOPE share this mission of equity. HOPE sources capital from major banks, philanthropy, and government and reinvests in communities often overlooked by traditional finance. Nearly half of all HBCUs are located within HOPE’s footprint of Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Tennessee, and soon Georgia — a region that is home to one-third of the nation’s persistent poverty counties.[3] That overlap makes collaboration not just possible but essential.

Figure 1: Nearly Half of Nation’s HBCUs Located in Deep South

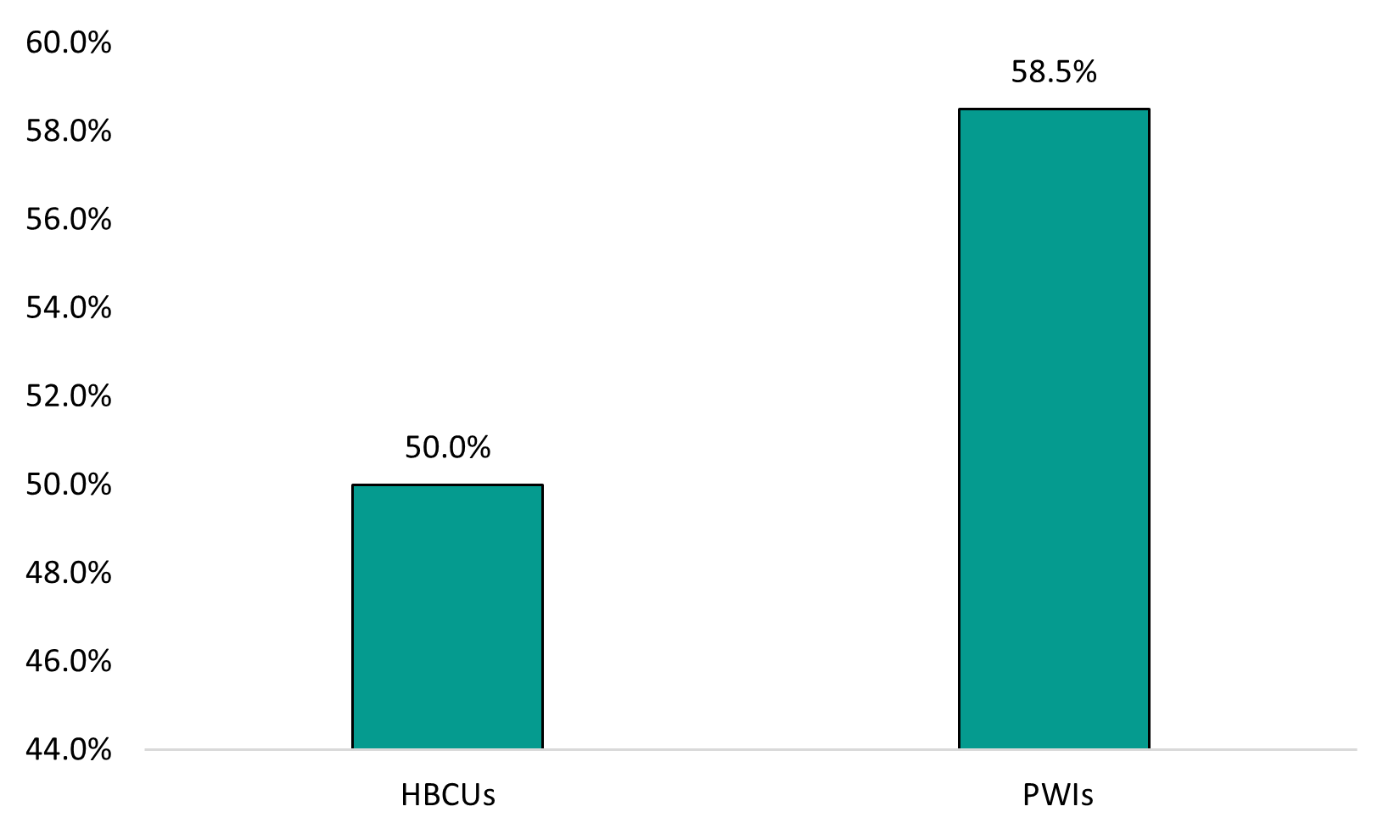

Despite their role as engines of economic mobility, HBCUs remain underfunded. A recent study found that the highest-funded HBCUs receive indirect cost recovery rates nearly nine percentage points lower than their predominantly white peers (See Figure 2).[4] Indirect cost recovery is the money institutions receive to cover overhead expenses such as maintaining labs, paying staff who manage grants, and supporting research infrastructure.

Figure 2: PWIs Outpace HBCUs in Indirect Cost Recovery Rates

Lower recovery rates limit HBCUs’ ability to sustain research and innovation.

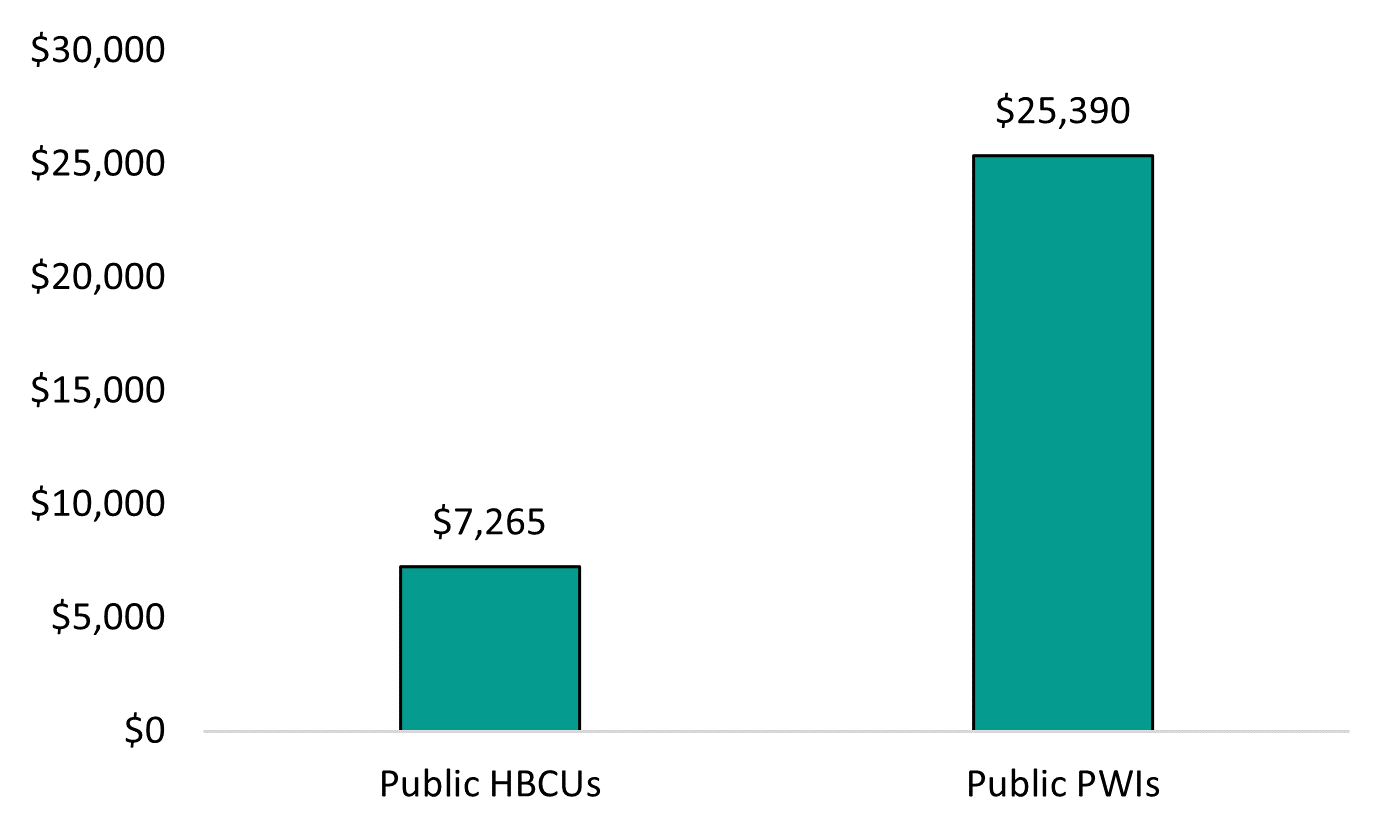

This gap means that HBCUs are left with fewer resources to sustain the very research projects that strengthen their competitiveness. If equalized, HBCUs would have $25.5 million more each year for research infrastructure and institutional growth. Stated differently, public HBCUs receive only about $7,000 in long-term support per student, compared to over $25,000 at other public schools (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: PWIs Hold Nearly Four Times More Endowment than HBCUs

Deep inequities in funding leave HBCUs with fewer resources to support communities and weather economic downturns.

HBCUs also hold less than one percent of the total wealth in higher education endowments.[5] By contrast, many non-HBCU peers have endowments worth billions, giving them far greater flexibility to weather downturns and expand programs.

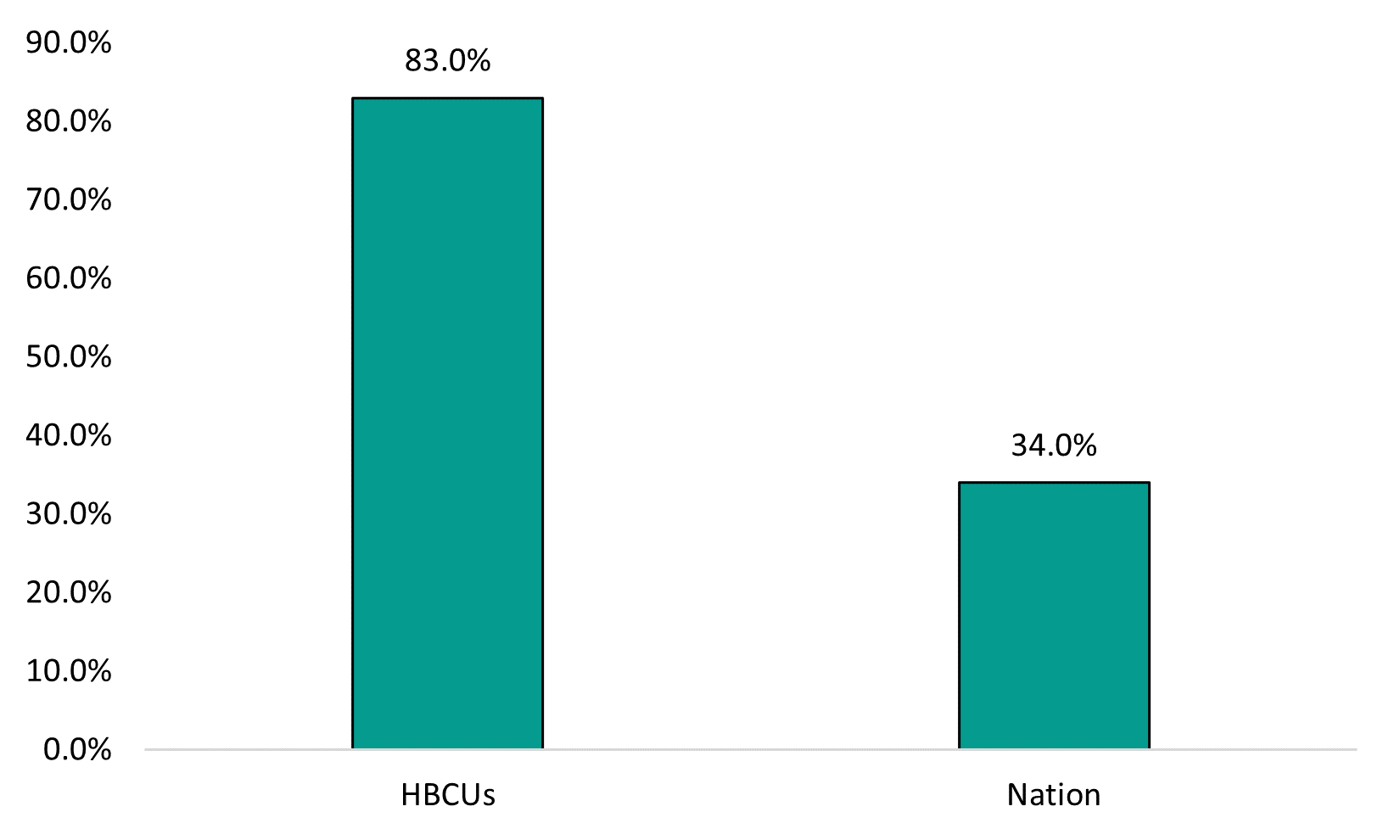

At the same time, HBCUs serve the students who need support the most. Eighty-three percent of HBCU students receive Pell Grants, compared to just 34 percent nationwide.[6] This means HBCUs are disproportionately serving first-generation and low-income students while operating with fewer resources.

Figure 4: HBCUs Exceed National Rate for Pell Grant Access

HBCUs are nearly 3x more likely to serve First-Gen, low-income students than other institutions.

This chronic underfunding doesn’t happen in isolation. The communities around HBCUs often face higher poverty rates, lower household incomes, and double the unemployment compared to those near predominantly white institutions.[7]

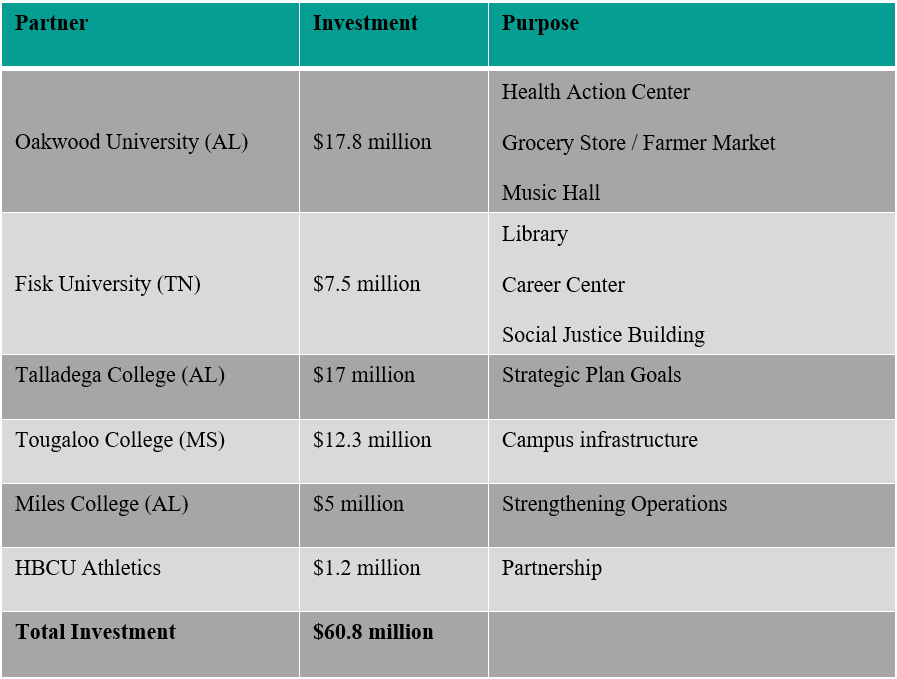

The Response: Investing in Institutions and Communities

In the last three years, HOPE has invested over $60 million in HBCUs (See Figure 5). These investments range from supporting cash flow and operational needs to funding campus facilities and infrastructure. HOPE also provides advisory services, helping HBCU leaders compete for national grant dollars.

Figure 5: Expanding Opportunities with HBCUs through Investments

At Tougaloo College, this collaboration has helped strengthen the institution’s ability to support students while serving as an anchor for redevelopment in surrounding neighborhoods. At Talladega College, investment has gone into improving campus infrastructure that directly benefits both students and the local economy. These stories illustrate how aligning missions leads to transformative outcomes: stronger institutions, empowered students, and revitalized communities.

The Bigger Picture

The impact of these collaborations goes beyond balance sheets. They build generational wealth. They catalyze entrepreneurship. They ensure that communities historically locked out of opportunity have a chance to thrive.

Policy leaders and funders should take note. CDFI-HBCU partnerships are not charity. They are smart, equity-driven investments that pay dividends for students, families, and entire regions. In a South where history and inequality run deep, these collaborations offer a model for how to turn resilience into lasting prosperity.

The lesson from Tougaloo, Talladega, and dozens of other HBCUs is clear: when institutions rooted in community join forces with mission-driven financial organizations, the results are transformative. Together, CDFIs and HBCUs are proving that alignment of mission and resources can expand what’s possible for the Deep South and the nation.

[1] “The history and impact of HBCUs.” theweek.com, https://theweek.com/education/hbcus-history-enrollment-increase

[2] Lomax, Michael L. “Black Colleges Matter: Debunking the Myth of the Demise of HBCUs – UNCF.” UNCF. November 14, 2017. https://uncf.org/the-latest/black-colleges-matter-debunking-the-myth-of-the-demise-of-hbcus.

[3] HOPE Analysis of Depart of Education/ NCES College Navigator HBCU listing, https://nces.ed.gov/COLLEGENAVIGATOR/?pg=1&s=all&sp=4

[4] Hauschildt KE, Messersmith J, Iwashyna TJ. Inequities in Indirect Cost Rates Between Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Other Institutions. Acad Med. 2024 Dec 1;99(12):1432-1437. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005717. Epub 2024 Mar 25

[5] Smith, Denise A. 2022. “Testimony: The Value of HBCUs Should Be Recognized through Greater Public Investment.” The Century Foundation. December 9, 2022. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/testimony-the-value-of-hbcus-should-be-recognized-through-greater-public-investment/.

[6] Alexander, River. 2024. “Beyond Affirmative Action: HBCUs and the Time For Equitable Funding.” Columbia Political Review. https://www.cpreview.org/articles/2024/9/beyond-affirmative-action-hbcus-and-the-time-for-equitable-funding.

[7] Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta calculations based on IPEDS 2017. U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 201-2017 5 year estimates, tables S1701, S2301, DP08, B1903