COVID-19 Unmasks an Existing Economic and Racial Justice Crisis

April 10th, 2020

In a recently published study, State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus, the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) finds that Deep South states trail other states in public health responses to COVID-19.[1] Mirroring the public health response gap, Southern states lag in providing economic support by neither suspending debt collection nor expanding social safety nets. The glaring disparities in the South shine a light on the disproportionate effects COVID-19 has on communities of color, specifically Black people. COVID-19 is very likely to continue to spread and devastate Black households and communities, highlighting existing social and economic stratification caused by centuries of policy decisions that have excluded and discriminated by race and by place.

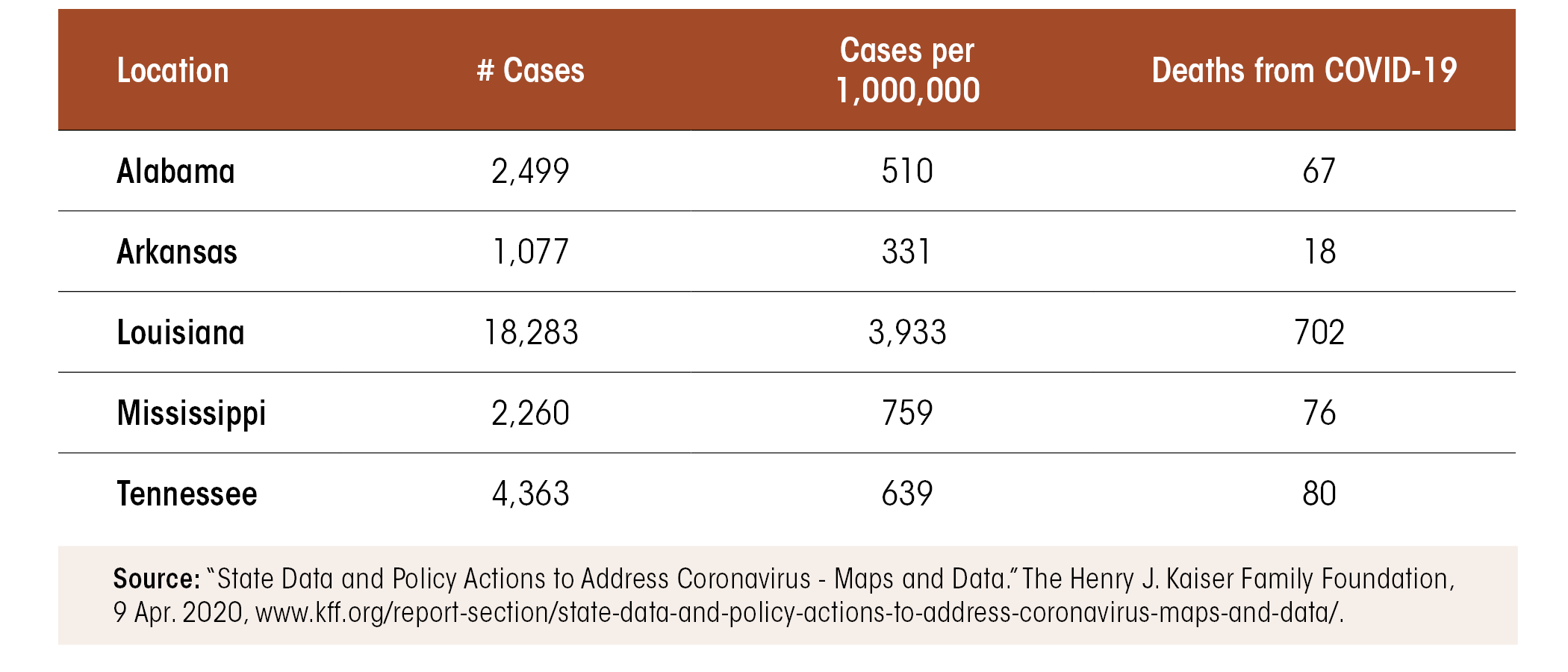

Confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the Deep South are climbing. See Table 1. As discussed in our previous blog, the challenges are further exacerbated by the Deep South’s strained health care infrastructure, where nearly half of the region’s counties do not have an Intensive Care Unit or hospital. On top of living in areas with limited access to health insurance and health care, Black and Brown people also encounter medical bias and disproportionately suffer from pre-existing conditions that makes COVID-19 so deadly. This accumulation of public health and other policy failures amplifies the massive loss Black communities will see.

Table 1: COVID-19 Cases per Capita as of April 9, 2020

The number of residents per state with the virus as a proportion of their population is in part a reflection of the coming strain on the state’s economy, and most acutely for communities of color and low-income workers. Poor, Black communities in Memphis, Tenn., are not receiving COVID-19 testing at the same rate of suburban communities, according to a heat map released by the Shelby County Health Department. This week, Shelby County announced that an alarming 71% of the county’s 21 deaths were Black people, even though Black people represent about 50% of the county’s population.[2] Farther South, data shows Black people make up only 32.4% of the Louisiana population, but 70.48% (452) of the 642 COVID-19 related deaths.[3] For neighboring states, Mississippi and Alabama death rates among Black residents are 72%[4] and 52%[5], respectively. Arkansas has not yet made this data available. As the demographic data of COVID-19 cases and deaths continues to be released, policy responses must account for the racial inequities that existed before this crisis and now serve as the pre-existing conditions for COVID-19 to take such a fatal hold on Black communities.

There are several factors to why low-income communities of color are disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Black and Brown people work in service sector jobs at higher rates that are now qualified as essential. Service jobs, such as health care support, janitorial services, and grocery store clerks, puts workers at risk of catching the virus and makes social distancing impossible.[6] In contrast, white populations are more likely to hold managerial or professional jobs allowing them to shelter in place and work from home.[7] As Black and Brown people are much less likely to work in these positions or have the ability to survive weeks without income, they risk increased or prolonged exposure to COVID-19, while also facing heightened barriers to access the medical care needed to stop it. In addition to providing essential services on the frontline of the pandemic, Black Americans in the Deep South have the lowest homeownership rates coming in contact with more people than those in single-family homes, live in communities with higher rent burden, and travel farther for groceries due to food deserts. Emphasized in a blog from our most recent policy series, more than 65% of Black households in Deep South states are liquid asset poor, another structural barrier that adds to the ramifications of the crisis.

Without adequate policy responses, COVID-19 reveals and exacerbates the existing economic and racial justice crisis in Deep South communities, and very likely will leave communities of color further marginalized than before. Yet, now more than ever, Black people and other communities must engage urgently in advocacy, innovative organizing, and with the resilience that has prevailed years of marginalization.

[1] “State Data and Policy Actions to Address Coronavirus – Maps and Data.” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 8 Apr. 2020, www.kff.org/report-section/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus-maps-and-data/.

[2] “COVID-19 Data Page.” LiveStories, insight.livestories.com/s/v2/covid-19-data-page/8a6ba562-bc6f-4e58-bdcc-c211b6be539c.

[3] “Coronavirus (COVID-19): Department of Health: State of Louisiana.” ldh.la.gov/coronavirus/?fbclid=IwAR2H4txiISOxNzpo9-JDYHMwdzkHNnpME1asNwUcrsG9RsV3-3itFV3cknE.

[4] Hensley, Erica. “Black Mississippians at Greater Risk: 72% of Deaths, 56% of State’s COVID-19 Cases.” Mississippi Today, 8 Apr. 2020, mississippitoday.org/2020/04/08/black-mississippians-at-greater-risk-72-of-deaths-56-of-states-covid-19-cases/.

[5] “Alabama Numbers Show Race Disparity in COVID-19 Deaths.” WBHM 90.3, 8 Apr. 2020, wbhm.org/2020/alabama-numbers-show-race-disparity-covid-19-deaths/.

[6] Tomer, Adie, and Joseph Kane. “How to Protect Essential Workers during COVID-19.” Brookings, Brookings, 31 Mar. 2020, www.brookings.edu/research/how-to-protect-essential-workers-during-covid-19/.

[7] “Not Everybody Can Work from Home: Black and Hispanic Workers Are Much Less Likely to Be Able to Telework.” Economic Policy Institute, www.epi.org/blog/black-and-hispanic-workers-are-much-less-likely-to-be-able-to-work-from-home/.