Fed Report Shows Low Income Families Are Taking the Hit From COVID-19 Job Losses

May 22nd, 2020

In his testimony earlier this week to the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell said of the COVID-19 crisis, “All of us are affected, but the burdens are falling most heavily on those least able to carry them.[1]” Because of long-standing economic and racial disparities, a greater proportion of people of color are dying as a result of COVID-19 infection. These same disparities are causing greater financial threats due to COVID-19 for low-income people and people of color.

Last week, the Federal Reserve released a report on financial wellbeing from their annual Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED). This year’s SHED report includes data from a supplemental update about the financial effects of the COVID-19 crisis.

COVID-19 Job Losses and Paid Leave

The report found that 20 percent of workers reported they lost their job or were furloughed as of the beginning of April 2020. However, this number was even higher for lower income workers. Almost 40 percent of workers earning under $40,000 reported losing their job or being furloughed.[2]

The report found that 20 percent of workers reported they lost their job or were furloughed as of the beginning of April 2020. However, this number was even higher for lower income workers. Almost 40 percent of workers earning under $40,000 reported losing their job or being furloughed.[2]

It is important to note that the April 2020 supplement only includes data on job losses and other financial issues as of March 2020, and thus includes only a preliminary look at the full effects of the financial crisis caused by COVID-19.

Another important employment issue in the wake of COVID-19 is access to paid leave for illness or to care for someone else who is sick. Access was found to differ based on a worker’s educational attainment. According to the study, “Workers who lack paid leave are more likely to face financial hardships or deplete financial resources if they become sick with coronavirus symptoms.”[3]

Financial Resiliency

With job losses and reduced hours, people will be less likely to be able to pay their bills and/or will have to deplete their existing financial resources to stay afloat. In the study, researchers looked at whether people reported that they would be able to pay an unexpected expense of $400 with cash (or equivalents) as a measure of a family’s financial resiliency. According to the study, of those who lost their job or had their hours reduced, only 46 percent reported they would be able to pay an unexpected $400 expense with cash.[4]

This measure of financial resiliency varied by race and educational attainment even before COVID-19. Almost 60 percent of Black respondents with a high school degree or less said they would not be able to pay all of their monthly bills if they had an unexpected $400 expense, compared with 35 percent of white respondents.[5] For respondents with a Bachelor’s degree or more, 23 percent of Black respondents would not be able to pay all of their bills if they encountered a $400 unexpected expense, compared with 11 percent of white respondents.

Access to credit

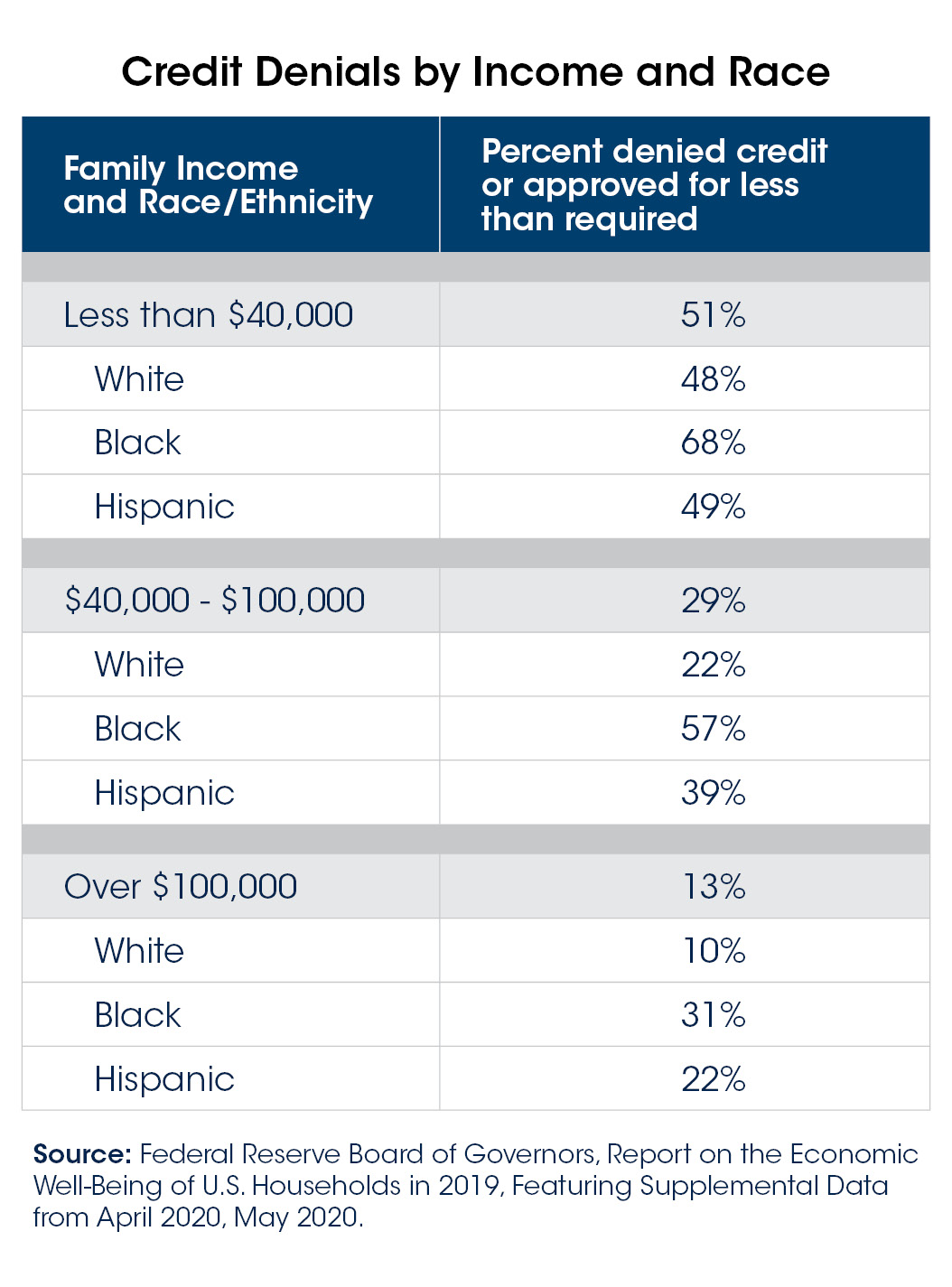

Many families who are unable to pay their monthly bills due to a job loss or an unexpected expense turn to credit in order to temporarily stay afloat. According to the study, “on average, individuals with capacity to borrow on a credit card were more prepared for financial  disruptions.”[6] However access to credit also varies by race. The study found that people of color and low-income borrowers were more likely to have been denied credit or approved for less than they requested. Fifty one (51) percent of those earning less than $40,000 were denied credit or approved for less than they requested compared with 20 percent of those earning $40,000-$100,000 and 13 percent of those earning more than $100,000. For respondents of all incomes, 57 percent of Black and 40 percent of Hispanic borrowers had been denied credit or approved for less versus only 24 percent of white borrowers. Higher income Black credit applicants (earning over $100,000) were denied credit at higher rates than lower-income white applicants (earning between $40,000 and $100,000). These denial rates were 19 percent and 17 percent respectively. The disparities grow when considering those denied credit or approved for less than requested. For these, 31 percent of higher income Black applicants were denied or received less than they asked for, compared with 22 percent of lower income white applicants.[7]

disruptions.”[6] However access to credit also varies by race. The study found that people of color and low-income borrowers were more likely to have been denied credit or approved for less than they requested. Fifty one (51) percent of those earning less than $40,000 were denied credit or approved for less than they requested compared with 20 percent of those earning $40,000-$100,000 and 13 percent of those earning more than $100,000. For respondents of all incomes, 57 percent of Black and 40 percent of Hispanic borrowers had been denied credit or approved for less versus only 24 percent of white borrowers. Higher income Black credit applicants (earning over $100,000) were denied credit at higher rates than lower-income white applicants (earning between $40,000 and $100,000). These denial rates were 19 percent and 17 percent respectively. The disparities grow when considering those denied credit or approved for less than requested. For these, 31 percent of higher income Black applicants were denied or received less than they asked for, compared with 22 percent of lower income white applicants.[7]

Access to other mainstream financial products also varies by income and race. Fourteen (14) percent of Black and ten percent of Hispanic respondents were unbanked (not having a checking, savings, or money market account) compared with six percent of respondents overall. Similarly, 14 percent of persons with under $40,000 in income were unbanked compared with only one percent of persons with higher income[8]. This is important because about half of unbanked respondents were forced to use alternative financial services such as payday lenders, check cashers, and pawn shop and auto title loans. Many of these services have predatory features that make their services expensive and hard to pay back.

This crisis is far from over and the recovery period is likely to be long. The important findings from this study show us once again that the COVID-19 crisis is exacerbating existing economic and racial disparities. Policy responses are needed that will help families in crisis by providing financial support and limiting harm from predatory lending practices, including an interest rate cap on payday loans, fair lending protections, and debt relief measures, like forbearances and forgiveness, to help families stay afloat during the crisis. How we respond to the COVID-19 crisis today will affect families’ physical health as well as their financial health now and in the long term.

[1] Statement by Jerome H. Powell, Chair Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate, May 19, 2020 https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Powell%20Testimony%205-19-20.pdf [2] Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019, Featuring Supplemental Data from April 2020, May 2020 https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/2019-report-economic-well-being-us-households-202005.pdf, page 53 [3] Ibid., page 55 [4] Ibid., page 55, Table 2 [5] Federal Reserve Board of Governors, Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2019, Featuring Supplemental Data from April 2020, May 2020, page 24, Figure 16 [6] Ibid., page 27 [7] Idid., page 28, Table 12 [8] Ibid., page 28